At Woodlawn, we are honored to have experts in many different areas who contribute to the research, restoration and education at Woodlawn. On this blog, join Woodlawn’s architectural historian Anthony Pellino as he explores the influence of the art deco period on the monuments, mausolea and sculpture at Woodlawn.

Glamorous, syncopated, energetic.

Don’t these words suggest the idea of being ready for anything?

Jungles of flowers,

Forms that soar into the air,

Rhythm, contrast, color……

Visuals that give the idea that you could leave earth altogether.

What I’m describing is Art Deco architecture.

What could possibly convince someone that such jauntiness is appropriate for her final resting place?

My beloved Woodlawn Cemetery is famous for its stonework, sculpture, landscaping, all lavishly executed by the best designers and artisans. The monuments that those of us in the Conservancy vaunt, typically, are found in the center of the park. You don’t have to go far to find them. Almost without exception, they’re classical in style, the products of Nineteenth Century Americans’ desire to show Europeans that our culture could equal theirs.

All of this ended abruptly with the Crash of 1929, but the seeds of change in design in fact had started long before.

With the end of World War One, the Jazz Age and American post-war prosperity, New York burgeoned with new funds, real estate development and above all people. There was a huge increase in money available to the Middle Class. The newly prosperous were seeking forms and products within popular culture; the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris served this need in spades.

Art Deco was above all intended to sell products to a market that wanted new things. The trauma of the war had left enormous disillusionment with the old order, to say the least. People were eager to move on, or barring that, to escape or be distracted. Global economic uncertainty and political changes within Europe and Asia left people anxious, particularly after 1929. For those of us who have lived through 2008, this may sound familiar. The bold colors, sense of movement and freshness of Art Deco all served a pervasive need for fantasy.

What would any of this matter to a person commissioning a funeral monument? I’m thinking these days that our current anxieties about money, governments, climate change have encouraged a similar response within the world of design and architecture. The extraordinarily fluid forms that are now possible with design and engineering software that can calculate for the solidity and safety of structures that would never have been possible before clearly serve a need within world culture. Ask any antique dealer these days: although people are eager to consume things, virtually no one cares to have anything old.

What would any of this matter to a person commissioning a funeral monument? I’m thinking these days that our current anxieties about money, governments, climate change have encouraged a similar response within the world of design and architecture. The extraordinarily fluid forms that are now possible with design and engineering software that can calculate for the solidity and safety of structures that would never have been possible before clearly serve a need within world culture. Ask any antique dealer these days: although people are eager to consume things, virtually no one cares to have anything old.

Moreover, nowadays, no one is going to die. Cryonics uses technology, the one thing that is surely guaranteed to save us, so that we can be revived from death immediately after scientists just catch up with our demands. Who needs funerary art? Who even thinks about it? In the 1920’s and ‘30’s they didn’t have that option, although it was coming. The stories of Walt Disney’s cryonic preservation are false, although someone named James Bedford was indeed frozen following his death in 1967.

Americans were perhaps closer to an older set of values in the years before World War II. The idea of Judgment Day, the date on which every human being would rise from the dead and face his or her maker in order to be sent to either Heaven or Hell might still have been floating around in the back of the mind of the average Woodlawn patron.

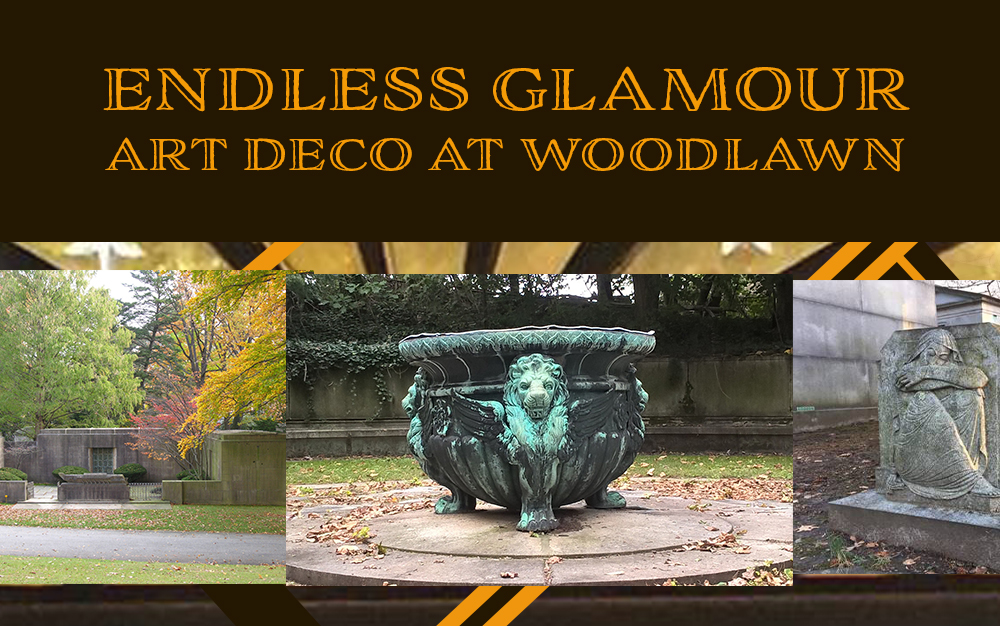

You have to go a little out of the way to find the Art Deco Woodlawn, but it’s there, as real as anything. Picture the grand landscape of the Untermyer site with its sweeping steps of broad double tombs rising, ever climbing upward, up and around a massive curve, leading to the bronze pavilion Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney designed that looks like a rocket rising above the heavy earth, ready to depart for the Moon.

I imagine the person commissioning an Art Deco mausoleum as a patron considering it to be a temporary shelter. How fresh, how jaunty it would be to wake from your crypt a thousand years in the future, all energized and ready to face your maker with a clean conscience; to cast aside your zig-zagged slab, open the starburst door, step down those syncopated steps and look upward at the glamorous skies of a new New York!

-Anthony Pellino